Machine Monitoring Provides an Objective Lens

Automatic, real-time shopfloor data collection tempers the bias that blinds manufacturers to the real reasons for downtime.

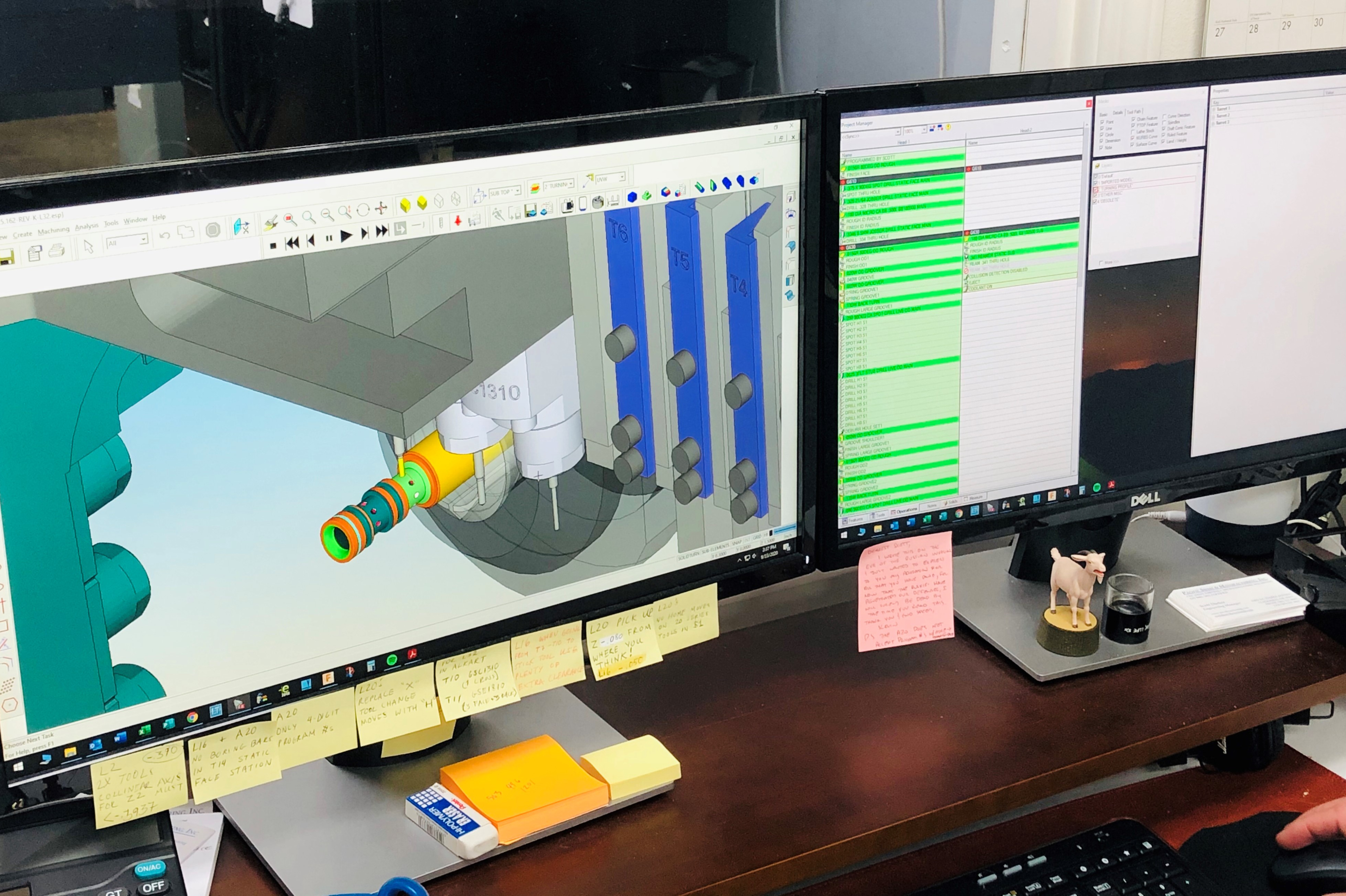

Bias, misperception and ignorance (willful or otherwise) are human problems, but today’s manufacturers have a technological solution. Capability to pull data from the shop floor automatically and in real time can provide a natural check on decision makers’ erroneous assumptions.

This was one takeaway of a recent conversation with Jim Finnerty, product manager at machine monitoring system developerWintriss Controls Group. Based on his experience with the company’s ShopFloorConnect system, bias begins at the point of data collection. “If you have machine operators entering information, you’re going to get varying levels of accuracy,” he says.

Featured Content

One reason for that is the same reason why shopfloor personnel sometimes resist monitoring technology in the first place: worry about being judged. However, results of numerous installations of the company’s ShopFloor Connect System at metal fabricating and machining businesses show that “downtime is almost never the operator's fault,” he says.

Consider a case in which an alarm triggers a machine stop while the operator is busy elsewhere with an urgent problem. After correcting the alarm condition and restarting the machine, the employee naturally worries about the potential consequences of leaving it down for so long. The employee indicates that the machine was down for 10 minutes due to a tooling problem. In reality, it had been down for more than an hour due to lack of an available operator. Such incidents create significant blind spots during downstream analysis and planning.

Automatic machine data collection leaves less room for such blind spots, and for worries about unwarranted finger-pointing. A lost hour of production could never escape notice if the data-collection system logs it automatically. It is also likely that a company with this capability would have understood the need for more hands on the shop floor long before the hour would have been lost in the first place.

To carry the example further, say the shop has configured the system to require choosing from a menu of downtime reasons to restart the machine after it has been idle for too long. Whether directly or through subsequent investigation, these reasons typically vindicate rather than implicate shopfloor personnel by identifying problems with, say, availability of tooling or materials, or even a deeper machine or process problem that warrants further investigation. There is little risk of busy people making simple data-entry errors or forgetting minor incidents that occur over the course of a long and tiresome shift.

“The downtime events you remember are not the problem,” Mr. Finnerty says. “It’s all the stuff you’ve gotten used to that’s killing you.”

Unfortunately, these “minor incidents” tend to be among the most significant contributors to downtime. They also tend to escape notice due to another form of human bias: the tendency to overemphasize catastrophe, particularly when events occurred earlier in a shift. “The downtime events you remember are not the problem,” Mr. Finnerty says. “It’s all the stuff you’ve gotten used to that’s killing you.”

For instance, everyone in the shop will remember a spindle crash. Meanwhile, seemingly insignificant downtime events might go unnoticed, even to the point of becoming accepted as part of the process. “If you can shave five minutes off a task you do 100 times a day, that really adds up,” he says.

Fallacious thinking can also result in misplaced priorities. For example, Mr. Finnerty recalls a case in which a production manager insisted that a particularly finicky piece of equipment run slower than it otherwise might in order to reduce the cost of maintaining it. However, analysis of machine monitoring metrics revealed that, contrary to the production manager’s intuition, running faster would be well worth it. “Reducing maintenance is fantastic, but the goal is to make money, not necessarily to preserve machinery,” Mr. Finnerty says.

All that said, the extent to which a machine monitoring system can address our tendency to misjudge and to err depends on how the system is configured. The problem with this is that people being people can get in the way from the very outset.

The solution to this dilemma is not technology, but other people. Shopfloor feedback is critical, as are outside perspectives, such as those a supplier might provide. For instance, during one recent implementation, Mr. Finnerty says deciding which downtime reasons to list at each workstation interface “took a committee.”

“They came up with about 100 of them,” he continues. “I jokingly told them their leading cause of downtime was likely to be deciding which of the 100 to pick! We generally recommend having five choices to keep the process as simple as possible.”